Maple Barister

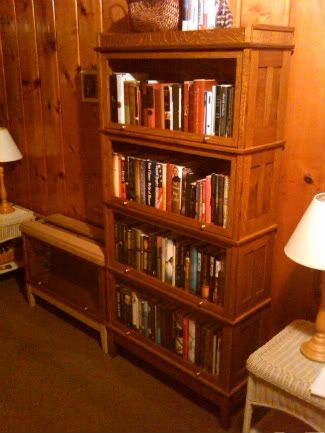

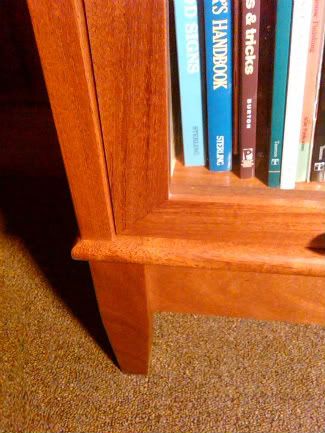

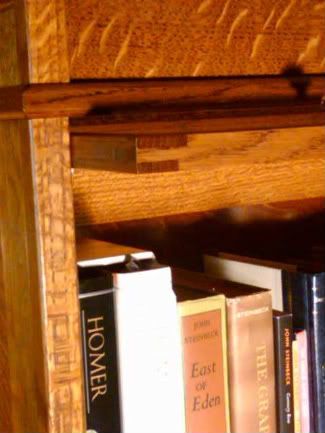

Here is the completed quartersawn solid white oak barrister with frame and panel sides that I recently completed. (Terrible pic, taken in a narrow hallway with bad light!)

![Image]()

I have completed 5 out of the 7 total that I plan to build in this style. I will return to building the remaining two after I complete the Maple Plywood ones that I'm blogging about now. I have decided to put these on hold to build the maple ones for my sister as a Christmas present. When I finish her maple bookcase I will continue to blog during the process of completing my remaining barristers to complete my set. (22 boxes total in 6 stacks)

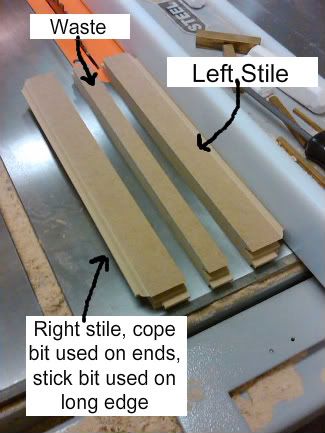

The maple barristers for my sister will differ from my solid oak ones in the following ways:

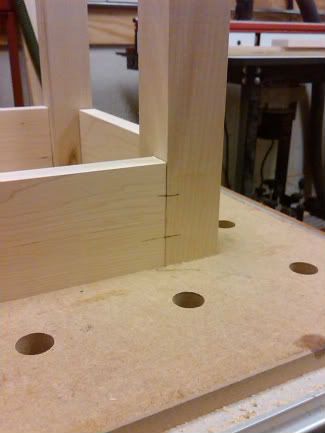

1. They will be mostly constructed with cabinet grade maple plywood as opposed to solid wood. (This will change a lot of the joinery used among other things that I will highlight.)

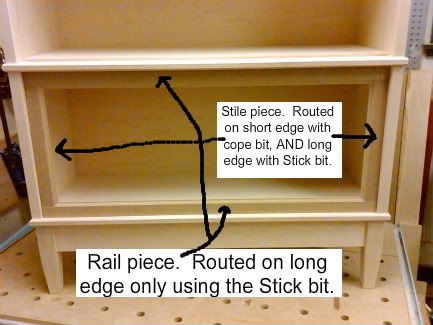

2. The sides will not be frame and panel like the solid oak barristers, they will instead be just plain maple ply wood.

![Image]()

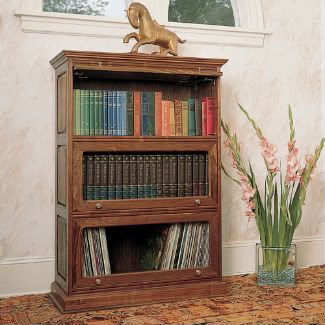

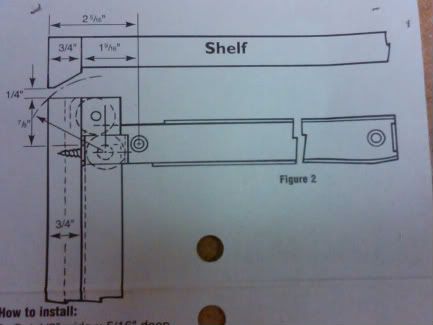

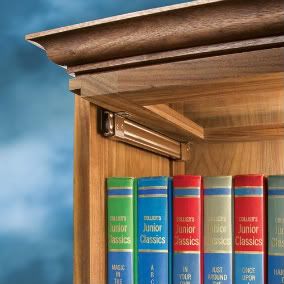

3. I'm not very happy with the way the doors operate on the sets I've already made, so I'm going to try to use Rockler's barrister slides.

![Image]()

4. I want to include a veneer birds eye maple top to this set. I'll probably use an MDF core. I have never done any veneering so this will be a learn as I go thing!

5. This will only be a 3 high stack so that the birds eye maple top will be more visible.

To download a set of plans go to: http://plansnow.com/bstbookcase.html

My next post will begin the construction of the boxes.

Here is the completed quartersawn solid white oak barrister with frame and panel sides that I recently completed. (Terrible pic, taken in a narrow hallway with bad light!)

I have completed 5 out of the 7 total that I plan to build in this style. I will return to building the remaining two after I complete the Maple Plywood ones that I'm blogging about now. I have decided to put these on hold to build the maple ones for my sister as a Christmas present. When I finish her maple bookcase I will continue to blog during the process of completing my remaining barristers to complete my set. (22 boxes total in 6 stacks)

The maple barristers for my sister will differ from my solid oak ones in the following ways:

1. They will be mostly constructed with cabinet grade maple plywood as opposed to solid wood. (This will change a lot of the joinery used among other things that I will highlight.)

2. The sides will not be frame and panel like the solid oak barristers, they will instead be just plain maple ply wood.

3. I'm not very happy with the way the doors operate on the sets I've already made, so I'm going to try to use Rockler's barrister slides.

4. I want to include a veneer birds eye maple top to this set. I'll probably use an MDF core. I have never done any veneering so this will be a learn as I go thing!

5. This will only be a 3 high stack so that the birds eye maple top will be more visible.

To download a set of plans go to: http://plansnow.com/bstbookcase.html

My next post will begin the construction of the boxes.