Wow! As always, I'm stunned by the quality and usefulness of the feedback that I find here…

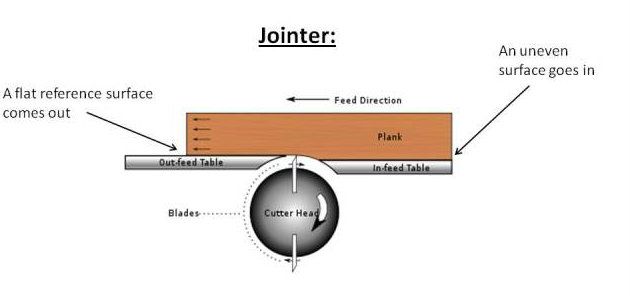

So let me see if I'm getting this right… it seems as though the primary difference between a jointer and a planer is not the essence of the machine, but the fences/rollers that allow you to establish a true reference line. They seem to both have an infeed table, an outfeed table, and a rotary cutter. In a jointer, you establish a true line by running the board through the cutter (with tables properly aligned) while holding it firmly against the fence, which is previously established to be perpendicular to the beds.

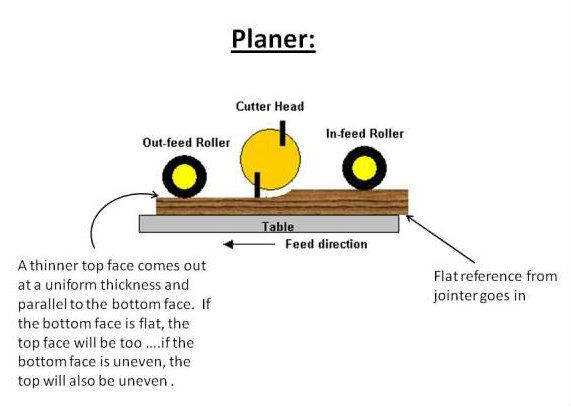

A planer, by contrast, takes as its reference line not the fence but the opposite face of the workpiece. Hence the twisted in, twisted out issue.

I'm interested in really figuring out this whole issue of true lines… I know this may sound a little "out there" to some, but I'm pretty interested in ancient thought and philosophy, especially the development of mathematics. Now, I'm no good at math whatsoever, but I do think it makes a good story, and interesting reading. Imagining how those ancient people cut square beams for their building… or square stone blocks for that matter… I just find that stuff fascinating. And it's not like it's easy stuff to get a handle on, even if it is all ancient… it takes thought, and experience, and observation. While I went to school for history and I've always been a big reader, I've been a working stiff all my life. Drives me crazy how little respect the manual arts receive. The builders, the cooks, the farmers, the plumbers, the seamstresses, the mechanics… We literally make the world go round. And we know stuff the ivory-tower types don't. We're not a bunch of idiots. It takes a lot of smarts, keeping the world turning. One of my favorite stories: when they built Oxford, they used great big oak beams, from great big ancient oaks. The problem with oak is that, after eight hundred years or so, it just basically fades away. So, eight hundred years after the founding of Oxford, the venerable masters found themselves in a big dilemma. Where would they find oaks of such stature these days? By this time, such woods were rare in Europe. For a year or more they worried over the problem, until finally news of it filtered down to the staff, and to the groundskeepers. They went in to the great halls, and found the venerable masters, and introduced themselves (for they had never met). "We knew about the oak when we built the halls," they said, "and we are ready." They led the learned professors, the great men of science who had despaired over how to repair the halls, to a hidden grove of great oaks-planted by the prescient and learned groundskeepers, eight hundred years ago. Moral of the story: there's a heck of a lot to learn from old-timers.

I wonder if this "jointer-planer" generational thing might not speak to just such a situation. I'd suspect that if the old-timers call them "jointer-planers," there's at least something to it. Maybe not what I expect… I wonder, though. There are three holes in the fence of my jointer. Parallel to the bed. I've puzzled over their purpose. Could they be there to accept some sort of rollers, a la a planer? Looking at the image above, a planer could just as easily have the cutter below, the beds offset, and the rollers in parallel.